he typeface owes its existence to a very current challenge. This is the story of a typeface that is all at once ancient yet still modern and current. Aad van Dommelen was recently faced with this task when working on the design of a corporate identity for a client. One condition of the brief was to use a Flemish letter from the baroque period. Although Christophe Plantin did not live in the 17th Century, the important book printer and his font of the same name immediately came to mind. However, it was not what the client had in mind. Neither was the proposed alternative DTL VandenKeere.

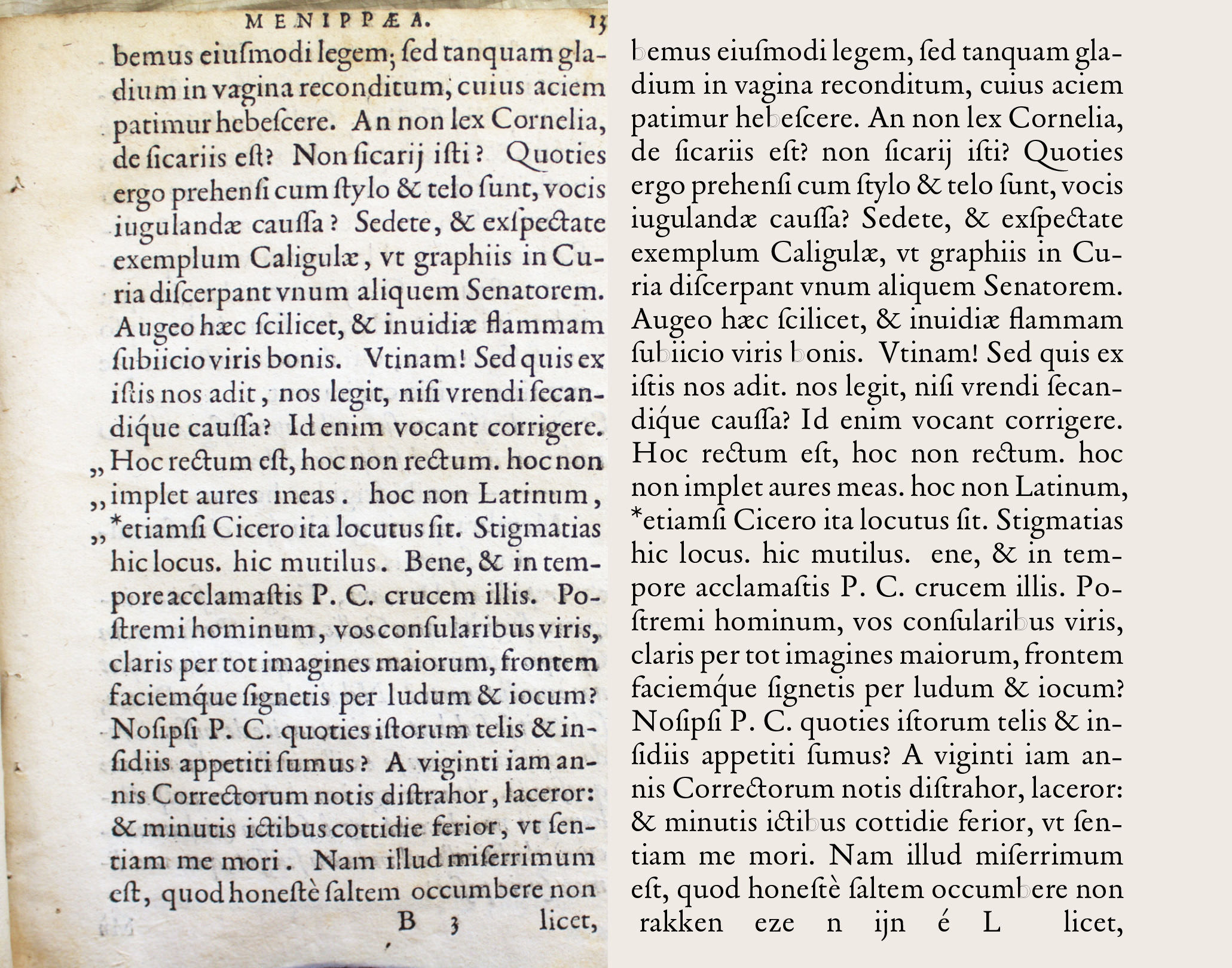

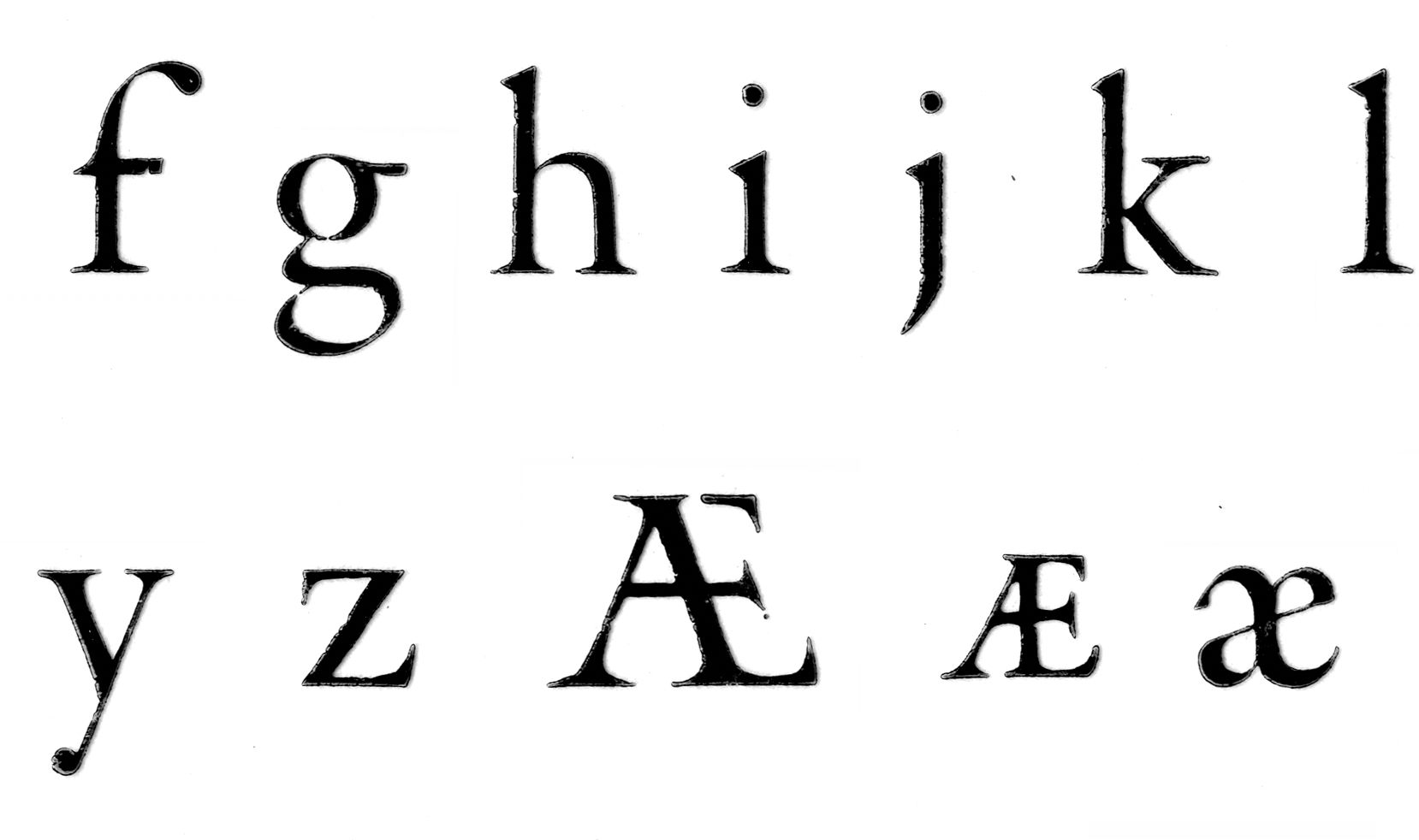

The only typeface that seemed to fit the bill was designed by Robert Granjon (1513–1590). The problem was that the existing digitization by Linotype deviated too much from the original and showed some inconsistencies. Digitizing the old templates seemed to be the best solution.

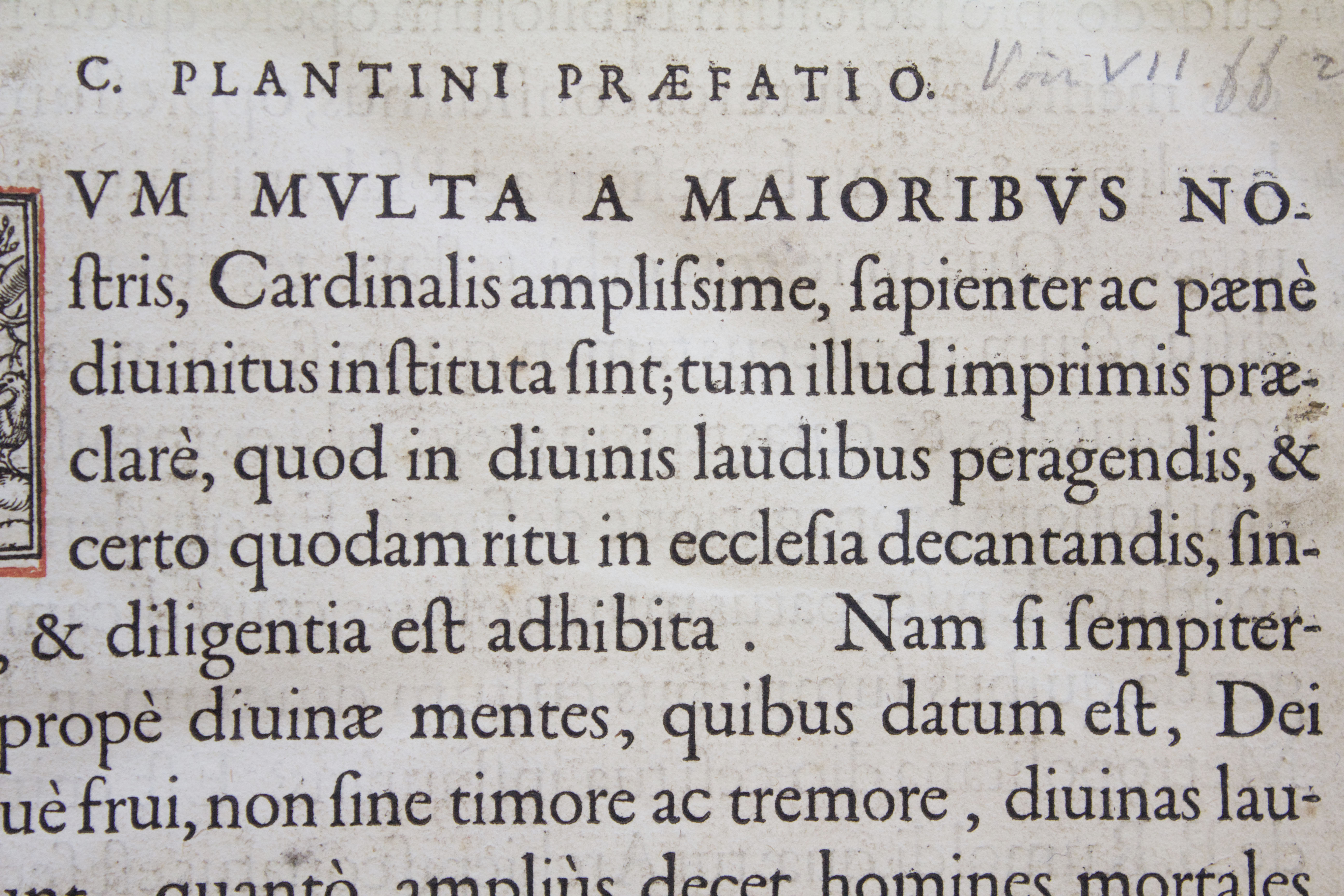

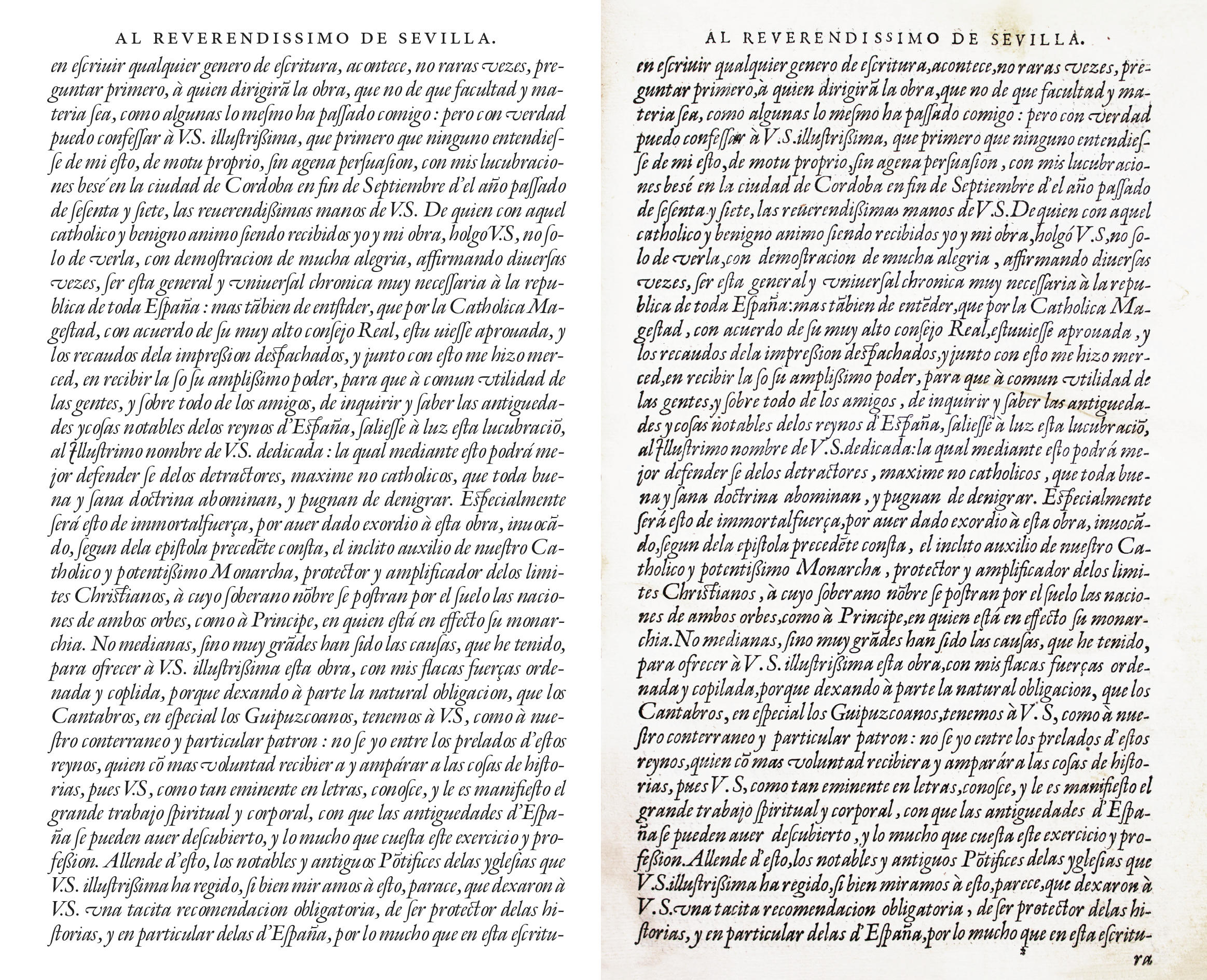

Aad van Dommelen’s first attempts to do this were based on photos of printed Plantin books. However, not all of the characters were used, and he had doubts about the quality of the type design presented to him. He wanted to get as close as possible to the designer’s original intent. For this he had to get closer to the origin of the typeface and go to Plantin-Moretus-Museum in Antwerp, where some original punches and matrices are still kept today.